ome voices don’t just sing. They echo. They pierce. They carry weight that was never theirs alone. Sinéad O’Connor’s voice was one of those. It didn’t just hold melody—it held grief, prophecy, rage, faith, defiance, tenderness. And for those of us listening, it held us too.

I don’t remember the first time I heard her, not in a cinematic way. It wasn’t a single song that struck like lightning—it was more like her voice had always been around me, humming low through the world. But at some point, I started really listening. And once I did, I couldn’t stop.

There was something in her that felt dangerous in the best way—because it was honest. She didn’t just sing about pain; she showed it. She didn’t polish it up or make it pretty for anyone’s comfort. It was raw. It was spiritual. It was real.

People called her brave. And she was. But bravery makes it sound like she chose that kind of exposure, like she welcomed the consequences. I’m not sure she did. I think she simply couldn’t lie.

When she tore up the Pope’s photo on SNL, I was too young to witness it live. I didn’t see the footage until a little later, and even then, I was still too young to fully grasp the weight of what she’d done. But I knew it mattered. There was something electric and dangerous in it—something true.

I grew up Catholic. And as I got older—growing up in the church, then beginning to reckon with what had been hidden and who had been hurt—that moment came rushing back to me. How brave. How brave. Not performative. Not for show. Just the raw, terrifying truth, offered up in front of millions. The backlash was immediate—and unforgiving.

Years later, I’d find myself returning to her—not just to “Nothing Compares 2 U” (though, of course, that too), but to the deeper cuts, the emotional ruptures.

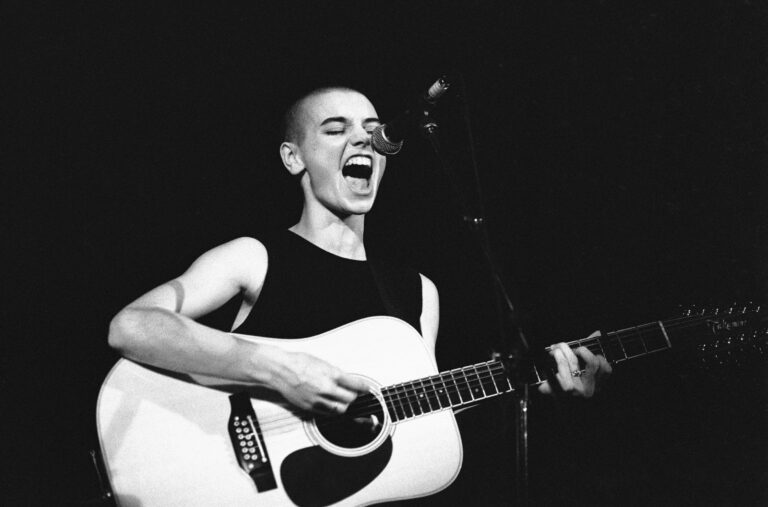

Troy still astounds me. Not just her voice as an instrument, though it’s that too—but the fire in it. The sheer force of it. Her voice could be so soft it felt ghosted into the air—barely there, like breath against glass. And then, in an instant, she’d tear through the quiet. Not showy. Not polished. Just that snap into something so vast it feels like it’s pulling the breath right out of you. The way she burns through the track, the way her voice cracks open and dares you to look away—it’s still unmatched.

And then there’s I Am Stretched on Your Grave. I don’t think my brain has ever fully comprehended the beauty and heartbreak in that song. It feels like something ancient and holy—grief set to rhythm. Her voice haunts, but it also honors. Like she’s singing to someone she’s still trying to keep alive, and in doing so, she keeps a part of herself alive too.

There are so many songs like that—“Black Boys on Mopeds,” “The Last Day of Our Acquaintance,” “Drink Before the War,” “What Doesn’t Belong to Me,” “No Man’s Woman,” “All Apologies,” “Emma’s Song”—and so many more. Songs that cut and comfort. Songs that still feel like warnings, confessions, survival strategies. And so on, and so on, and so on.

When she died, I didn’t want to write anything right away. It felt too close, too complicated. I wasn’t ready to make sense of it. I’m still not. But her absence is loud. It hums underneath things. Her voice is still playing in the corners of my mind like a memory I don’t want to lose.

What a voice can carry isn’t just sound. It’s sorrow. Resistance. Sacred anger. Hope. Loneliness. A whole generation’s quiet knowing.

Sinéad carried all of that. She carried too much. And she carried it with grace that was never gentle—but always true.

I still don’t have the right words for what she meant to me. But I can press play. I can sit in the silence after the song ends. I can remember.

And I can keep listening.

“But I will rise

And I will return

The Phoenix from the flame

I have learned

I will rise”

—Sinéad O’Connor, “Troy”

Header Photo Credit: Published by Houston Chronicle in November 1987. Photographer unkown.